My good friend Terry King has mentioned [on this tribute site] our introduction to Claude Ranger in 1970:

“I was playing jazz violin in Montreal around 1971, when I met Claude along with my friend, bassist Mike Morse. At that time we had never played with a musician of Claude’s stature (I’m not sure I’ve ever played with anyone of his stature since, either).”

We were the house band in a jazz coffee house in Val David called Jazz et Café. Some amazing people trooped through there, including Marius Coulthier, Peter Leitch, a very young Steve Hall, and Brian Barley. Brian amazed us, of course, and told us about Claude’s playing and writing. He showed us some of Claude’s tunes, and explained some things about Claude’s unique and insightful concept of harmony, based on the extensions of a seventh chord.

Terry and I went down to Old Montreal, and heard him with Billie Robinson, Peter Leitch, and Freddie McHugh. Growing up in NJ/NYC, I had already heard many great musicians — but nothing like this. The energy and creativity never flagged for a second, nor did the utter beauty of sound from the drums.

Shortly afterwards, Terry and I asked Claude to play a set at a college concert. To our amazement he said yes, and even agreed to do a rehearsal. We played in the basement of the McGill student centre. Claude was affable but quiet, setting up with seeming unconcern. The first tune we called was Claude’s “Le Pingouin,: which we had learned from a record of Claude, Brian, and bassist Daniel Lessard. The bass line is a simple chromatic pattern in half steps. I started playing it, and after a few measures, Claude started to play. That first few moments was one of the defining moments of my life. He was playing the most complex things I had ever heard from a drummer, yet it fit so beautifully and simply with the bass line he composed.

We finished the rehearsal, and played the concert a few days later, in a kind of ecstatic daze. We finished our set, and had to find the promoter to get our salary. 20 or 30 dollars for all three of us? Something like that; we gave it all to Claude, naturally. In any event, Claude waited backstage. The next act had already started, a loud rock band. When we found Claude, he was sitting with his back to the wall, which shaking from the volume of the rock band–composing music! Thunderstruck, we asked how he could do this, and he said something like “only what you hear inside matters.”

Many folks have rightly mentioned Claude’s capacity to turn any musical event into something extraordinary and artistic. I remember once going to hear Claude up on St. Hubert someplace, with Terry and Jerry Labelle. The group was just a trio, an amiable but utterly pedestrian organist, singer — and Claude.

The music was the most banal bar trash of the day. One of the numbers was a merengue. The hook to the commercial merengue beat is four sixteenth-notes on the snare drum at the end of the second bar of the pattern, leading to the downbeat: ducka-ducka-DUM; ducka-ducka-DUM. When the tune started, my friends and I suddenly felt something utterly marvellous, and didn’t know immediately what it was. We soon figured it out. Claude was playing all of the standard accents for merengue, but was playing the principle figure on the ride cymbal instead of the snare. The first sixteenth note, he left out altogether. The next was piano-pianissimo, the next pianissimo, and the fourth and last piano, in a slight, incedibly controlled crescendo. The effect was magical, profoundly musical, and danceable, too! Even if someone else had thought of this ingenious variation, it demands virtuoso control of dynamics to pull it off. Who else but Claude could do that?

Claude always played the complete music, never just a drum part. I had the opportunity to work four nights with Claude in Ottawa, a trio gig with baritone saxophonist Charles Papasoff. It was all standards and jazz tunes, and Claude played with such sensitivity to the music that you actually hear the chord changes, both in his accompaniment and solos. Here was a drummer on the level of the greatest in jazz, a composer and theorist of the same calibre, and a profoundly inspiring bandleader and teacher to several generations of musicians.

I once spent half a year composing a postcard to Claude, in French. The substance was: if I have been able to glimpse a small part of the true glory of music, revered friend, it is thanks to you above all.

MW Morse

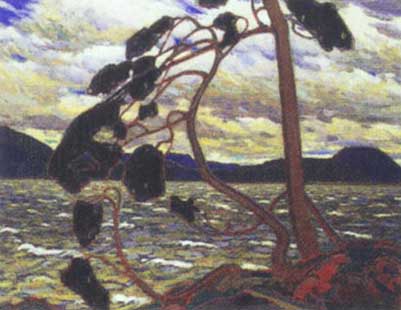

Here is a tune inspired by Claude Ranger’s musical ideas.